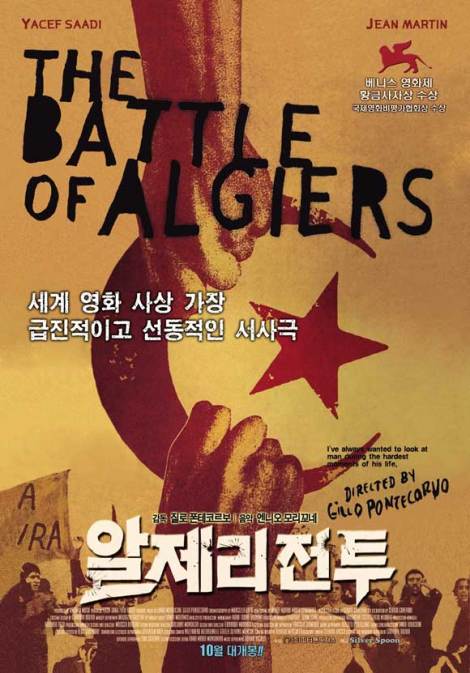

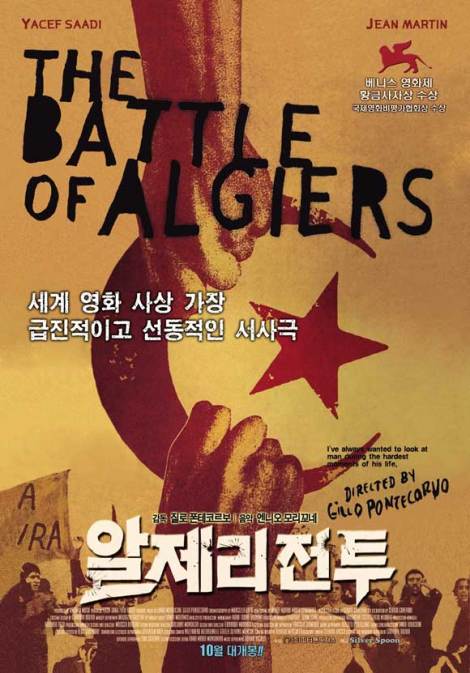

STUDY NOTES.

Made in 1966, the film has remained a classic of political cinema. It is one of the most powerful records on film of a people’s struggle to be free. And it has continued to exert a strong influence on filmmakers in mainstream and alternative cinemas. The varied audiences over the years have included the Black Panthers in the USA: and from the opposite end of the political spectrum, the Pentagon. The film sets out the struggle, the violence and the suffering, ” the pains and the lacerations which the birth of the Algerian nation brought to all its people” [Hibbin, 1981] Today, even for viewers who know little about the actual historical events depicted, it remains an enlightening experience. Its continuing relevance is in part due to the film being much copied, but its content, form and style are the outcome of the specific context of 1960s.

Synopsis:

From 1954 to 1962 there was a war in Algeria against the French occupation of that country. It was led by the Front de Libération Nationale [FLN], a coalition of nationalist forces. The film’s particular focus is the on the battle in the city of Algiers, between the FLN, organised in the Casbah, and the French paratroopers. The film is set in the city between 1954 and 1960, a period of intense violence in the struggle between the Algerian and the French colonial rulers.

The film opens in 1957 as French paratroopers use torture to discover the hideout of the leader of Algerian resistance in the city, Ali la Pointe. Ali and three comrades are trapped in their hideout and a flashback returns us to 1954. The plot follows the development of armed resistance organised by the FLN and Ali’s recruitment and training as a volunteer. The City-based resistance is centred in the Casbah, a tightly packed warren of streets and buildings. The FLN strike at the colonial police, who retaliate by using bombs that target Algerian civilians. The FLN then organises bomb strikes against French targets in the city.

The French bring in the elite paratroopers under the command of Colonel Mathieu. During an 8-day strike organised by the FLN the paras go on the offensive. The Paras identify the pyramid structure of the FLN organisation and they use torture to extract information from suspects. Gradually they identify and capture the FLN leadership in the city. By 1957 Ali is the sole leader at liberty and he is executed when the paratroopers blow up his hideout.

The FLN rebellion seems defeated but a coda in 1960 shows the mass demonstrations erupting from the Casbah onto the streets. And a voice-over announces that independence was achieved in 1962.

The Algerian War of Independence.

Algeria was colonised by the French in the early C19th. After a rebellion in 1871, Algeria was incorporated into Metropolitan France and maintained a large French-speaking settler population among the indigenous Arab and mainly Muslim people. A rising tide of National Liberation dominated the world following the 1939 – 1945 War. In 1945 there was a large-scale massacre by the French of Algerians demonstrating for greater freedom and civil rights. The most notable nationalist force was the Algerian People’s Party, committed to legal means in its struggle. Disillusioned with such tactics, a small group launched an armed rebellion in 1954. The rebels formed a coalition of groups into the Front de Liberation Nationale, the FLN: though there were also opposing organisations like the M.N.A. [Mouvement National Algérien]. There were different political strands within the FLN, notably a secular, socialist oriented faction, and those with a more traditional Islamic orientation. And there were violent vendettas between the FLN and the M.N.A., and within the FLN. However, the FLN became the leading organisation in the liberation struggle, and was seen as the representative of the Algerian people. Their initial successes bought a brutal response from the French colonialists, who used modern military technology such as aircraft and tanks combined with surveillance and torture. Probably the most vicious example of this was the suppression of the Casbah-based resistance in Algiers itself by the elite corps of paratroopers. But the contradictions of the French repression created both protests and conflict within France itself. There was always leftist opposition to the colonial policy, and organised support by Algerian migrants living in metropolitan France. Rebellions by right-wing army and settler groups aimed at preventing a negotiated peace led to the ascent to power in France of General Charles de Gaulle. Whilst the FLN was unable to defeat the French directly in battle, the French could not suppress the rebellion. Support from other Arab countries, especially Tunisia, Morocco and Nasser’s Egypt was important. In 1962 a cease-fire was agreed and full independence was achieved on July 3rd 1962.

Pontecorvo with the production team on set.

The Property.

The initial source for the film is a memoir by a participant in the Algiers resistance, Saadi Yacef, Souvenirs de la Bataille d’Alger, [1962]. After Independence, with the support of the new Government, Yacef set up Casbah Films with the idea of turning his memoir into a film. An aide, Salah Baazi, took a script to Italy, seeking technical and artistic help. One possible director for the film was Gillo Pontecorvo. He had already visited Algiers in 1962 and together with his collaborator Franco Solinas, had an idea for a film set during the War of Independence. The two approaches were rather different. Yacef envisaged a heroic portrayal of the FLN resistance: Pontecorvo a story about a French photojournalist and ex-paratrooper, possibly using a Hollywood star.

However, the two sides came together and Solinas produced a new script, which used Yacef’s memoir as a staring point. But there was also extensive research on the ground. Pontecorvo and Solinas spent several months interviewing participants in Algeria, [about 10,000 eyewitnesses]; they also visited Paris and interviewed members of the military who had served in Algiers. Apparently there were five major revision of the script before both the sides were satisfied. The finished film closely follows this final script. The funding for the production was partly provided by Casbar Films and partly by funds raised in Italy by Pontecorvo. The Italian producer Antonio Musu, involved in Pontecorvo’s previous film Kapó, was key to raising the money and enabling the final production go-ahead.

Preparing a scene.

Production.

The director, Gillo Pontecorvo, bought a small team with him from Italy, including his fellow scriptwriter Franco Solinas and cameraman Marcello Gatti. But the bulk of the production and practically all the cast were local people. The film was co-produced by the Casbah Film Co. headed by Yacef Saadi, who had been the organiser of the Casbah resistance. During filming Gatti was giving lessons in cinematography to Algerian after the day’s shoot. The controlling hands of Pontecorvo [in particular] and Solinas is evident, but the film is also the product of a collective memory and a collective viewpoint.

The only professional actor in the film is Jean Martin who plays Colonel Mathieu. His distinction included experience in French film and theatre, but also being a signatory to an anti-war letter by French artists. Inhabitants of the Casbah play the Algerians. Saadi Yacef plays himself in the film. Pontecorvo recruited the other lead actors. He tended to use typage, a technique developed in Soviet cinema, where performers are chosen because their looks seem to represent the ‘type’ in the story. Western tourists in the city were recruited to play the parts of Europeans.

Pontecorvo aimed to produce a visual style to the film that resembled documentary or newsreel footage. He had experimented with these techniques in his previous film, Kapó, set in a Nazi Concentration camp. The Battle of Algiers was shot in 16 mm and then dupes [duplicates] were made of the negative. This produced the grainy effect associated with newsreel. However, it also tended to exaggerate contrasts, so a very soft focus film stock was used and the camera apertures were stopped down [reduced]. The whole process tended towards a rather flat image, and because of the bright sunlight in which most of the film was shot, even open-air sets tended to be covered in white sheets [or scrims] and filters placed over the camera lens to reduce the light.

Pontecorvo also wanted to mirror the position of the newsreel camera and produce a sense of distance in the audience. [An approach he calls the ‘dictatorship of truth’]. Much of the filming used a telephoto lens to effect this, though such a lens also foreshortens the seeming distance between characters and between objects. The film utilises the long shot [distance] and the long take [duration], but also sequences of relatively fast editing and close-ups for particular characters or gestures. The camera is mostly handheld; this was not just an aesthetic choice, as the narrow streets of the Casbah did not allow the use of a dolly [mobile camera platform]. The camera is always on the move, creating a dynamic sense of movement and action.

There are a large number of scenes in the film involving multiple characters. Since not all the crew and very few of the cast had professional experience, this demanded careful planning and organisation. This generated much noise, including the use of megaphones to orchestrate performers. But the actual sound during filming was only used as a cue track and the dialogue, effects and music dubbed on later. This practice was common in Italian Cinema in this period.

Several key scenes proved difficult to capture in the style Pontecorvo wished. The dramatic scene where the Algerian women change into European clothes before their mission to plant the bombs was originally written with dialogue. But instead, Pontecorvo used a musical accompaniment [a ‘baba saleem,’ Arab music with a strong percussion element] that was played as the women performed to create the particular tense sequence. The final demonstration, when a single woman dances out from the crowd was shot three times, finally uses drifting smoke to create the desired visual effect.

There were a few post-production effects; one important one being the optical dissolve that is achieved as a close-up of Ali La Pointe changes to the flashback of 1954. There was, of course, the soundtrack work, and the title cards that frequently add to the visual information. Mario Serandrei commenced the editing whilst waiting for Pontecorvo in Rome. The latter discovered on viewing two reels that Serandrei was following the conventions of mainstream continuity, which Pontecorvo wished to avoid. In fact, Serandrei was taken ill and died suddenly. Pontecorvo worked with the assistant editor, Mario Mura, on those two reels and the rest of the film. He also worked with the composer Ennio Morricone to develop the score, which is such an important part of the film. The use of chorales by Morricone as viewers contemplate the chaos and death after the bomb explosions are key emotional points in the film. Pontecorvo [as in all his feature films] also composed themes used in the film, and chose some of the music.

11th December 1960

Analysis

The Battle of Algiers would seem to be informed by the challenging and passionate dictates of Frantz Fanon.

“To fight for national culture means in the first place to fight for the liberation of the nation, that material keystone which makes the building of a culture possible. There is no other fight for culture, which can develop apart from the popular struggle. To take an example: all those men and women who are fighting with their bare hands against French colonialism in Algeria are not by any means strangers to the national culture of Algeria. The national Algerian culture is taking on the form and content as the battles are being fought out, in prisons, under the guillotine, and in every French outpost which is captured or destroyed.” [Fanon, 1961].

Franco Solinas and Gillo Pontecorvo’s script organises events into an episodic plot, with linkage provided by on-screen titles and voice-overs. This structure effects one of the maxims of Bertolt Brecht, that the potential to re-arrange events in the plot is one way to contest conventional narratives. It also mirrors the ebb and flows of the struggle in Algiers and in the city. The alternation of the European and ‘native’ city, a distinction from Fanon’s writings, is reinforced in the mise en scène. This is also true of the characters’ dialogue, direct and committed on the part of the Algerians, conversational and sometimes circular on the part of the Europeans. The film presents two opposing cultures, crucially centred on the figures of Ali la Pointe and Colonel Mathieu.

Whilst the main narrative privileges Ali La Pointe as an individual hero and draws out the emotional sympathies of the audience, the opening and closing codas are crucial in suggesting the full meaning to us as viewers. We open in the territory of established society and cinema, as the controlling French paratrooper use torture to break the resistance. With the closing coda the Algerian people, ‘a choral personage’ in Pontecorvo’s word, have taken control. Seemingly spontaneous demonstrations throw down a fresh challenge to the French occupation. Hence the power as we see the bemused French policeman with his loudhailer whose uncomprehending question ‘What do you want?’ receives its dramatic answer in actions of the demonstrators and their calls of “Independence. Our Pride. Freedom!”.

The importance of the involvement of the people in the resistance is stated in the dialogue, by Ben M’Hidi, but reinforced visually by the way the lead characters and their actions are placed in the wider world of the Casbah and Algiers. The film develops a clear and supporting relationship for the FLN among ordinary Algerians. It is this relationship that an audience is meant to see as the basis for the apparently spontaneous fresh uprising in the film’s coda. Leading to the statement that ‘an Algerian Nation was born’, the resolution is clearly the triumph of the people’s struggle.

As leaders of this struggle the FLN are the good guys in this film. But Pontecorvo and his colleagues achieve a dispassionate gaze that has continually evoked praise over the years. The fact that the French colonialists are in the wrong is signalled by the racism experienced by Ali. This is reinforced when the French police are the first to target civilians. And then by the brutal methods of the paratroopers who use of torture during the campaign. However, the film does not counterpoise a heroic to a non-heroic mode. Both sides are clearly involved in actions against civilians and the victims on each side are treated with comparable dignity. This is made especially powerful by the use of a chorale after both acts of ‘terrorism’, but also accompanying the scenes of torture by the French paratroopers. Whilst Pontecorvo may evoke the sympathy of the audience for both sets of victims, the film is clearly unwavering in the rightness of the FLN’s cause.

Paisa – people watch on the bank as the corpses of the Partisans float pass in the River Po.

The Battle of Algiers is clearly influenced by the movement known as Italian Neo-realism. Parallels can be seen both in the production process followed and in the style of the finished film. Neo-realism was coined in 1943 by the scriptwriter Antonio Pietrangeli when talking about the film Ossessione, directed by Luchini Visconti. Influenced itself by French poetic realism of the 1930s, full-flowered neo-realism had a documentary feel with non-professional actors, location shooting and the frequent use of the hand-held camera. This was a reaction against both the studio based artificial melodramas of mainstream Italian film and against the Fascist politics that dominated Italy up until 1944. Neo-realist directors like Roberto Rossellini and Victoria de Sica aimed to show a ‘slice of life’, social reality, in particular the condition of ordinary people, the working classes. Neo-realism had a considerable impact outside Italy, both because it offered a differing filmmaking process from the studio system that dominated popular cinema, and also because its style offered a sense of authenticity lacking in mainstream features. Neo-realism was to influence the new cinemas in ex-colonial countries. A number of young filmmakers trained at Cinecittá in Rome and took the ideas and practices of neo-realism back to their own cinemas.

Pontecorvo has recounted how he was struck by a screening of Rossellini’s Paisa. Not only can one see the approach of neo-realism in Pontecorvo’s film. There is a particularly strong sense of the style of the final episode of Paisa, which recounts the doomed resistance of Italian partisans against the occupying Germans late in W.W.II.

People watch as the paratroopers ‘execute’ an FLN cell.

Criticisms.

If The Battle of Algiers remains a widely acclaimed and seminal film it has also had its critics. One recurring reservation is the way it uses mainstream narrative form and style to present the drama to an audience. Some argue that to ‘make films politically’, [as advocated by Jean-Luc Godard], requires a different set of conventions, for example, in the fashion of Brecht’s theatrical work. One critic quoted by Joan Mellon criticised the film’s use of Ali La Pointe as a ‘hero’, “The presence of a hero “becomes a barrier to the clarity of what is politically, as opposed to romantically, significant. ” Pontecorvo responded to such criticisms, “It [also] seems to me that to renounce films that are made for the normal market in the normal way – narrative, dramatic, etc – to consider them not useful is a luxury of the rich, of people probably not really interested in political results. … If you consider this problem [the alliance of the working class with other classes] to be one of the most important, you must also see that it’s important to make films for the normal channel.” [Pontecorvo, 1984]. And Ali La Pointe is certainly not a conventional hero. Edward Said has argued that the heroes of the film are the oppressed Algerians. The Battle of Algiers certainly tends to arouse an audience by identification and passion on behalf of the oppressed Algerians, [a classic protest format].

There is a little space dedicated to questions of analysis in the film: [see below]. The Battle of Algiers has frequently been described as propaganda, usually in a conventional sense of supporting a particular point of view. However, in Soviet politics a rather different meaning was used. Propaganda was complex material and analysis for the more advanced stimulating ideas and analysis. This was counterpoised to agitation, less complex material that roused emotional involvement. Pontecorvo’s film is closer to agitation, and this would seem to be the intended function of the film. But whilst the film does operate through arousing emotions, it also has sequences that tend to create a more dispassionate distance for the spectator. The Battle of Algiers is an agitation for the values of Liberation, both for the Algerian people and, in a wider sense, for the all those oppressed by colonialism. In the context of the reactionary stances in most western countries, which were also deeply racist, The Battle of Algiers provides an affirmation of the struggle. This aspect is less powerful forty years on, just as the torture scenes are less shocking for most modern viewers. Developing conventions and other film’s use of similar techniques mean our susceptibilities are different from the 1960s.

In terms of analysis the film does pass over, without comment, important issues. The film does not address the contradictions within Algerian resistance, including opposition by some groups to the FLN. There is no real focus on the struggle in the countryside, which continued after the defeat in Algiers. The society of the occupation, and the settlers are not seriously analysed.

Actually there were considerable contradictions of class, gender and religion. Some criticism has especially focused on the question of women’s role in the struggle. But the film does include active women who are important in the struggle. What is missing is an examination of the particular problems for women that need to be faced: an obvious question would be the influence of Islamic mores typified by the veils that so many of the women wear. This contradiction underlies the powerful scene where the women dress in European style, but it is not examined elsewhere. Pontecorvo, aware of this contradiction; chose to ‘end the film symbolically, with one woman!’ That the film does not actually analyse this is partly a question of context. The film is reflecting the politics of the movements. These stressed the unity across struggles in a popular front against French colonialism. Thus the FLN members in the hideout are a young married man, a women, [probably unmarried], a young boy, [possibly an orphan] and an ex-criminal. The very stress on the unity of these disparate characters precludes the examinations of what divides them. The subsequent history of politically independent Algeria points to the problematic this creates, but this is something that is more easily addressed with hindsight.

Another issue raised in criticism is the film’s treatment of Islam. Such criticism seems to comment on the film from the standpoint of the present. In the 1960s liberation movements were more secular, more influenced by ideas and practices from the Soviet Union and China, rather than religious ideas, including Islam. Still, Islamic culture was fairly strong in Algeria. Saadi Yacef explained about the ‘tensions’ between religion and secularism within the FLN. “It’s the fault of the French who, since 1830, had discriminated against the Islamic religion. During the war, Islam was legally pushed aside, in a situation similar to apartheid. People conserved all the practices of the religion …and that remained constant.” Pontecorvo added, “At that time, the presence of religious beliefs in their revolutionary political ideology was extremely positive because it gave a solid foundation to that struggle.” Fanon’s idea of ‘building a national culture’ was to be inextricably entwined with traditional patterns including Islam. This was one factor in the internal struggles in the FLN. But the film passes over those during the battle and subsequently after independence. In fact, a coup by the military wing of the FLN deposed President Ben Bella whilst the film was in production. One scene does, though, present Ben M’hidi telling Ali that “once we’ve won, the real difficulties start.”

A recent book on Pontecorvo has suggested a critique of ‘terrorism’ in his work. Carlo Celli’s title ‘From Resistance to Terrorism’ gives flavour of his argument. However, contemporary ideas of terrorism are very much post-1960s and post-Battle of Algiers. Celli includes comments on Pontecorvo’s final feature film Ogro. This dealt with the Basque separatist Movement ETA. After finishing the film Pontecorvo made public self-criticism. However, this would seem to have much to do with Italian politics in the 1980s as with the Basque question. This was the period when there were the events involving the Red Brigade, right wing terror groups and the death of Aldo Moro. The content for Battle of Algiers was the wars between colonial powers like France and Britain, and the indigenous peoples fighting for freedom. As the film itself shows and Ben M’hidi explains to the journalists, the F.L.N. fought bombs with bombs. Many Algerians had been recruited into the allies’ World War 11 armies, where violence against civilian populations was endemic on both sides. Ben M’Hidi’s has another line in the film, “Wars aren’t won by terrorism, neither wars nor revolutions. Terrorism is a beginning but afterward all the people must act.”

In an interview Franco Solinas commented, “the most important fact among all others, which the film intends to emphasise, is the reason for Algeria’s final victory – armed struggle. I am convinced that Algeria did win with its own means because if the Algerians had not acted as they acted, suffered as they suffered, resisted and fought as they did, then Algeria might still be French today.” [On Criterion DVD].

The Paratroopers in the opening sequence.

Placing the film.

The Battle of Algiers does not fit easily into the familiar film genres. If it is a war movie, then it is a very unusual war, and of a type that mainstream cinema rarely offers. It does however use some common generic characteristics. In particular, whilst the film offers a ‘choral hero’ of the people, the plot does use the conflict between to opposing figures, Ali the revolutionary and Mathieu, the soldier. This was a familiar trope in Italian westerns, in which Franco Solinas also worked. And there are echoes of this conflict relationship in Pontecorvo’s subsequent film Queimada! ! [Burn 1968], also featuring a black revolutionary and white European adversary – Jose Dolores played by Evaristo Márques [a non-professional] and William Walker, played by Marlon Brando.

One type of film narrative, possibly a genre, which does link with The Battle of Algiers, is the melodrama of protest. The influential Soviet classic The Battleship Potemkin is a melodrama of protest, and there are clear influences in Pontecorvo’s film. A recent example would be Ken Loach’s The Wind that Shakes the Barley [dealing with the Republican forces in the Irish War of Independence and subsequent Civil War].

There is an alternative category of film in which Battle of Algiers can be placed. Two Argentinean’s, Fernando Solanas and Octave Getino argued in an important political manifesto [1983] that there was the dominant cinema Hollywood and then there were three types of cinema: ‘first cinema’, artistic films by auteurs; ‘second cinema’, national or independent cinemas separate from the dominant cinema; ‘third cinema’, direct oppositional film. Where might we place The Battle of Algiers in this typology? Fairly clearly, whilst the film’s narrative form and style are accessible to a mainstream audience, the film is very different from mainstream film, both in style and content. It does, as Solanas and Getino advocate, ‘directly and explicitly set out to fight the system.’

What about as an auteur film? Whilst Battle of Algiers is most frequently referred to as ‘a film by Gillo Pontecorvo’ in fact, it is the result a combination of different viewpoints, both Franco Solinas and Saadi Yacef being important contributors. Yacef’s role has often been overlooked, and not all versions of the film credit his source memoir. This and the participation of ordinary Algerians suggest both a ‘national’ cinema and an independent cinema. Many critics draw comparisons with Pontecorvo’s other films as exemplifying a pattern of ‘auteur’ filmmaking. Some of these can be attributed to Franco Solinas. And there are also striking differences with the other films. Notably there is the absence of a Hollywood star actor: the use of which created problems in Pontecorvo’s other films. This can be seen in Queimada where Marlon Brando famously fell out with the director over having to work with non-professional Evaristo Márques. Another aspect of Queimada! is that the ‘choral voice’ of the people seems much less developed than in The Battle of Algiers. Whilst the latter film ends on the mass demonstrations of the people of the Casbah, Queimada! ends with the death of the main protagonist, William Walker: a rather conventional motif. Collective action is a feature of all of Pontecorvo’s feature films, but none seem to dramatise this as powerfully and centrally as The Battle of Algiers.

This last point would introduce a qualification about assigning the film unproblematically to Third Cinema. In a parallel manifesto another Latin-American filmmaker, Jorge Sanjines argued forcibly for the involvement of the participants in creating film records of events. Sanjines worked as director on films made by the Ukamau film collective with Andean Indians:

” … many scenes were worked out on the actual sites of the historical events we were reconstructing, through discussions with those who had taken part in them and who had a good deal more right than us to decide how things should be done.” [Sanjines, 1983]. Pontecorvo was clearly the deciding voice on the film, and in that sense the film is still an authorial product, and it is in this sense that it circulates, as ‘a film of Gillo Pontecorvo’. Solanas and Getino [following the ideas of Frantz Fanon] also placed much emphasis on films by people fighting colonialism and neo-colonialism. To a great degree The Battle of Algiers was in the hands of the European crew of filmmakers, and it has circulated mainly under their auspices. There are other film dramatisations of the Algerian struggle. At the time of the release of Pontecorvo film there was an Algerian feature, Lakhdar-Hamina film, The Wind of Aurès. In fact, The Battle of Algiers was preferred over this Arab film for the prestigious Venice Film festival, where it won the award. And even now it is much harder to see Algerian films on this subject than Pontecorvo’s. Thus the film does not essay some of the conventionally very different formal and stylistic approaches to be found in films made by Arab and African directors.

The Battle of Algiers should probably be thought of as a transitional film. Whilst clearly embracing the value system of the oppressed Third World peoples it is still positioned within the cultural expression of the first and second cinemas. Originally Pontecorvo envisaged the film circulating in ‘film clubs and festivals’. Given that cinema was invented and generally controlled within the imperialist west this can be seen as a possibly positive step as the Third World filmmakers master and take possession of this cultural machinery. This would seem to be the attitude of the Algerians involved, as Pontecorvo’s film was also a training ground in cinema production and techniques.

On a personal note, on once more revisiting this classic film I found it still extremely moving and inspiring. It is also a record of a historic event in the C20th anti-colonial struggle.

References.

Roy Armes, Postcolonial Images Studies in North African Film, Indian University Press, 2005. It includes fair detail on Algerian cinema and the most notable films. Roy Armes has written a number of excellent books on North African cinemas, and other cinemas among the oppressed peoples.

Carlo Celli, Gillo Pontecorvo: From Resistance to Terrorism, Scarecrow Press 2003. The book includes a biography of Pontecorvo and discusses all his major films.

Frantz Fanon, On National Culture in The Wretched of the Earth, [translated Constance Farrington] Grove Press, New York, 1968. There is a 1996 film Franz Fanon Black Skin White Mask [UK / France, director Isaac Julien, which combines documentary material with re-enactments, a unsatisfactory mixture that does not fully elucidate Fanon and his ideas, but is an interesting introduction.

Sally Hibbin, Battle of Algiers (1966) in The Movie, Chapter 70, Orbis Publishing, UK, 1981.

Joan Mellon, Filmguide to The Battle of Algiers, Indiana University Press, Bloomington London 1973. Out of print, however there are copies in the British Library and the BFI Library.

Fernando Solanas & Octavio Getino, Towards a Third Cinema, in Twenty -five Years of the New Latin American Cinema, edited by Michael Chanan, C4 TV / BFI, 1983

Jorge Sanjines, Problems of Form and Content in Revolutionary Cinema, also In Chanan, 1983.

The Dictatorship of Truth, An Interview with Gillo Pontecorvo by Edward Said. Cineaste, Vol. XXV, No. 2, 2000

The Making of The Battle of Algiers by Irene Bignardi. Cineaste, Vol. XXV, No. 2, 2000. There is an abbreviated version of this at http://www.arts.arizona.edu/mar453/Making%20of%20Battle.htm

Terrorism and Torture in The Battle of Algiers, An Interview with Saadi Yacef by Cary Crowdus. Cineaste, Vol. XXIX, No. 3, Summer 2004

Rear Window, 1992. Pontecorvo – The Dictatorship of Truth. Channel 4. A programme about Gillo Pontecorvo and his films presented by Edward Said.

NB Media Education Journal, Issue 42 will have an overview of the films of Gillo Pontecorvo by the author.

There are a number of Websites that address the film and the filmmakers

http://www.wsws.org/articles/2004/jun2004/pont-j09.shtml has an interview with Gillo Pontecorvo and a review.

http://www.marxists.org/history/algeria/1956/ali.htm is part of a site on The War of Liberation and has an extract from Saadi’s Memoir.

http://www.filmreference.com/Writers-and-Production-Artists-Sh-Sy/Solinas-Franco.html has a profile of Franco Solinas.

http://www.dailyscript.com/scripts/boa.htmlhas an English version of the script for the film.

THE BATTLE OF ALGIERS (1966). Produced by Antonio Musu, Igor Films of Rome, and Saadi Yacef, the Casbah Film Company (Algiers). Filmed in Algiers in 1965. Screenplay – Franco Solinas and Gillo Pontecorvo. Direction – Gillo Pontecorvo. Director of Photography Marcello Gatti. Editing – Mario Serandrei, Mario Morra. Art Direction – Sergio Canevari. Music – Gillo Pontecorvo and Ennio Morricone. Special Effects Tarcisio Diamanti and Aldo Gasparri. Algerian Assistants Ali Yahia, Moussa Haddad, Azzedine Ferhi, Mohamed Zinet. Algerian “Opérateurs” Youssef Bouchouchi, Ali Maroc, Belkacem Bazi, Ali Bouksani. In French and Arabic. Time: 123 minutes.

CAST: Djafar – Saadi Yacef [sometimes shown as Yacef Saadi]: Ali La Pointe – Brahim Haggiag: Colonel Mathieu – Jean Martin: Captain Dubois – Tommaso Neri: Le Petit Omar – Mohamed Ben Kassen: Hassiba – Fawzia El Kader: Fathia – Michele Kerbash

The film won the Lion of St Mark at he 1966 Venice Film Festival. It also received three Academy Award Nominations, Best Foreign Film, Best Director, Best Screenplay. It was banned in France for over five years, which also led to its delayed release in the UK.

Argent Films have a DVD version, which also includes an interview with Pontecorvo. At one point he illustrates the editing style followed in the film. Note the subtitles do not provide a complete translation of dialogue and text.

Criterion has a three-disc DVD set. Its version is the 1999 restoration, with excellent visual and sound quality. There are also fresh subtitles, which translate the entire main dialogue and text. Extras include a Making of…, Remembering History, and Gillo Pontecorvo’s Return to Algiers in 1992 and a booklet with an excerpt from the script and an interview with Franco Solinas.

Interesting companion films: There are several films made in Algeria about the liberation struggle. During the war a group of French supporters made Algeria in Flames [Algérie en flammes, 1959]. A documentary compilation Dawn of the Damned [L’aube des damnés, 1965] was directed by the Algerian filmmaker Ahmed Rachedi. The Wind from Aurès / Assifat al-aouras [1966] by Mohamed Lakhdar-Hamina was a fictional story set during the war, and follows a mother who seeks her son captured by the French. The Way / La voie [1968] Slim Riad deals with his experiences of the French policy of internment. More followed in the 1970s, mostly treating the Algerian resistance in a heroic mode. However, except for Festivals, these films are almost never available in the UK.

The Battleship Potemkin / Bronenosets Potemkin, USSR 1925. Sergei Eisenstein. The most famous example of Soviet Montage. The film, like The Battle of Algiers, is a melodrama of protest. It uses typage, and whilst there are individual leading characters, the heroes and heroines of the film are the mutinying sailors and the supporting townspeople of Odessa.

The Betrayal / La Trahison, France 2005. Phillipe Faucon. One of several French films that deal with the atrocities committed by French police against Algerian migrants demonstrating in favour of the Algerian resistance. Many innocents’ participants were killed. The subject was taboo in France for decades. The suppression of the event is one theme in Michael Haneke’s 2005 Hidden [Caché].

Days of Glory / Indigènes, France / Belgium / Morocco / Algeria, 2006. Rachid Bouchareb. North Africans from Algeria and Morocco serve in the French army in World War II. Whilst exposing European racism the film fails to fill in the North African context. A much more biting depiction can be found in Camp de Thiaroye, Senegal 1988. Ousmane Sembène.

Queimada / Burn, Italy / France 1968. Gillo Pontecorvo. Produced with funding from Hollywood, hence the star Brando. The distributors cut the film by 20 minutes. Both Solinas and Morricone contributed to the film. The plot follows a slave rebellion on a fictional Portuguese island. Jose Dolores, the leader of the rebellion, is clearly modelled on the great Toussaint L’Ouverture, leader of the Haitian revolution. William Walker is based on an actual C19th US adventurer in Central America. The film is more analytical than The Battle of Algiers, but offers less focus on the ordinary people.

Paisa / Paisan, Italy 1946. Roberto Rossellini. There are six episodes, which follow the allied armies in the liberation of Italy in 1943. The final episode, a masterpiece among war films, deals with the resistance of Italian partisans, assisted by US soldiers, as they fight and die in the Po marshes.

Silences of the Palace / Saimt el Qusur, France / Tunisia, 1994. Moufida Tlati. Through flashbacks the film explores the situation of women in domestic service to the elite during the period of the Tunisian struggle against French Colonialism. A very different world from that of the Casbah depicted in Battle of Algiers.

The Wind That Shakes the Barley, UK, Eire, … 2006. Ken Loach.The national liberation struggle in 1920s Ireland. The film offers a firm commitment to the Irish rebels, but also shows ‘atrocities’ by both sides, and the new socialist culture developing during the struggle. Unlike The Battle of Algiers it also details the divisions within the rebels forces.

![Palestine film Fest1[1]](https://thirdcinema.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/palestine-film-fest11.jpg?w=1024&h=724)